The Navajo Code Talkers

Friday, November 11, 2011 at 9:18PM Tweet

Friday, November 11, 2011 at 9:18PM Tweet By Jim and Donna Poulton

Credit: nmai.si.edu

Credit: nmai.si.edu

They were at Guadalcanal, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, Okinawa .. They were in every assault the U.S. Marines conducted in the Pacific theatre from 1942 to 1945. The idea to use them came from Philip Johnston, the son of a missionary to the Navajos and one of the few non-Navajos who spoke their language. Johnston, a World War I veteran, knew of the dilemma the U.S. forces were facing: During the early months of World War II, Japanese intelligence experts broke every code the U.S. had devised. With access to the codes, and with plenty of fluent English speakers, the Japanese were able to use the U.S. communications to their own advantage – sabotaging messages, setting up ambushes, issuing false commands.

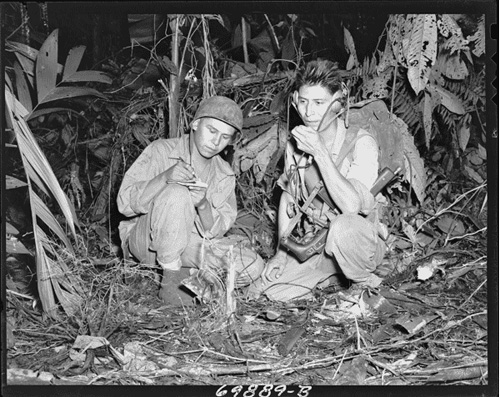

Photograph of Navajo Indian Code Talkers Henry Bake and George Kirk. Credit: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S)

Credit: US Navy Museum Web site. Photo #: USMC 127-MN 89670

Credit: US Navy Museum Web site. Photo #: USMC 127-MN 89670

In response, the U.S. devised more and more complex codes – to the point of absurdity. At Guadalcanal, military leaders complained that they now required more than two hours to de-code a single message. Something had to be done.

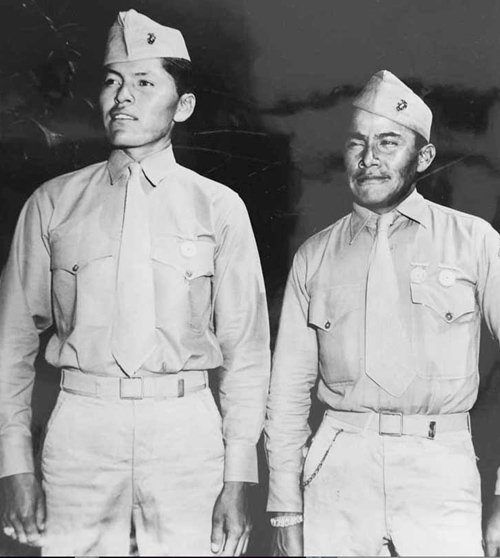

Private First Class George H. Kirk, USMC and Private First Class John V. Goodluck, USMC. Credit: Photo #: USMC 127-MN 94236

Private First Class George H. Kirk, USMC and Private First Class John V. Goodluck, USMC. Credit: Photo #: USMC 127-MN 94236

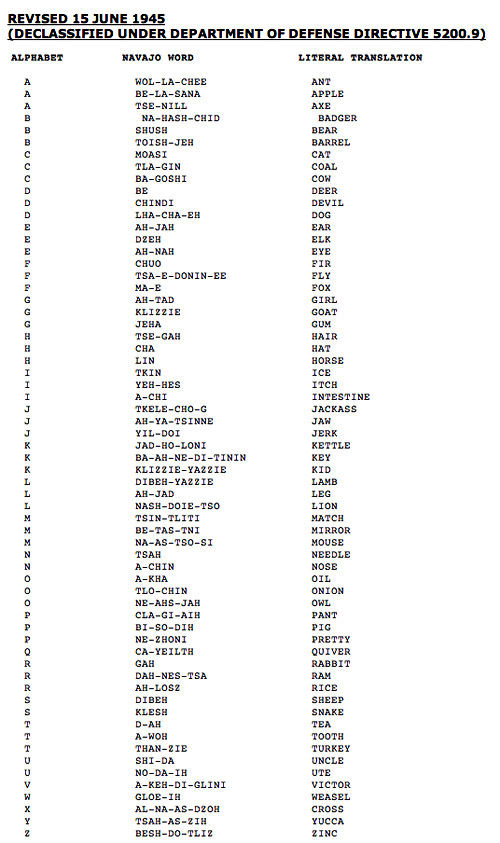

Philip Johnston believed that the Navajo language answered the military requirement for an undecipherable code because it is extremely complex, tonal (in that high and low tones of the same phoneme can mean different things), and has no alphabet or symbols. Needless to say, speaking and understanding Navajo requires extensive exposure and training. In 1942, it was estimated that only 30 non-Navajos in the world spoke Navajo – none Japanese.

Private First Class Alec E. Nez, USMC, and Private First Class William D. Yazzie, USMC. Credit: U.S. Marine Corps. Photo #: NH 107263

Private First Class Alec E. Nez, USMC, and Private First Class William D. Yazzie, USMC. Credit: U.S. Marine Corps. Photo #: NH 107263

Johnston convinced the U.S. forces to give the Navajos a try by demonstrating that they could encode, transmit, and decode a three-line English message in 20 seconds, increasing the military’s efficiency by a factor of 360,000 – or something of the sort. Within a matter of weeks, 200 Navajos were recruited.

Credit: U.S. Navy Museum Website

Private First Class Hosteen Kelwood, USMC, Private First Floyd Saupitty, USMC and Private First Class Alex Williams, USMC. Credit: U.S. Marine Corps Photo #: USMC 129851

Private First Class Hosteen Kelwood, USMC, Private First Floyd Saupitty, USMC and Private First Class Alex Williams, USMC. Credit: U.S. Marine Corps Photo #: USMC 129851

The rest, as they say, is history. The Navajo code talkers accrued praise throughout the war for their skill, speed and accuracy. At Iwo Jima, six code talkers working around the clock sent and received over 800 messages in the first two days of battle. The 5th Marine Division signal officer said of their dedication: ‘Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.’

Airman Jose Porcayo, assigned to USS Constitution shares a laugh with veterans who served in the U.S. Marine Corps as Navajo Code Talkers during World War II at a book signing during Albuquerque Navy Week. Navy Weeks are designed to show Americans the investment they have made in their Navy and increase awareness in cities that do not have a significant Navy presence, 4 October 2009. Photographed by MC1 Eric Brown, USN. Credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo #: NH 107218-KN (Color) Navajo Code Talkers

Airman Jose Porcayo, assigned to USS Constitution shares a laugh with veterans who served in the U.S. Marine Corps as Navajo Code Talkers during World War II at a book signing during Albuquerque Navy Week. Navy Weeks are designed to show Americans the investment they have made in their Navy and increase awareness in cities that do not have a significant Navy presence, 4 October 2009. Photographed by MC1 Eric Brown, USN. Credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo #: NH 107218-KN (Color) Navajo Code Talkers

The Japanese never cracked the Navajo code.

Credit: clydemcdonnell.blogspot.com

Credit: clydemcdonnell.blogspot.com

In 2001, President George Bush spoke at a ceremony honoring 21 surviving Navajo code talkers: ‘Today, America honors 21 Native Americans who, in a desperate hour, gave their country a service only they could give. In war, using their native language, they relayed secret messages that turned the course of battle. At home, they carried for decades the secret of their own heroism. Today, we give these exceptional Marines the recognition they earned so long ago.’

President George W. Bush presents Congressional Gold Medals to four of the five remaining former Navajo Code Talkers who served during World War II in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, 26 July 2001. Credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo #: NH 107229-KN (Color). Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

President George W. Bush presents Congressional Gold Medals to four of the five remaining former Navajo Code Talkers who served during World War II in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, 26 July 2001. Credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo #: NH 107229-KN (Color). Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Navajo Code Talker Monument, Window Rock, Arizona. Photo by Tom Grier/Winona, Minnesota: course1.winona.edu

Sources for more information about the Navajo Code Talkers: