The first in our series on Impressions of the West from great authors:

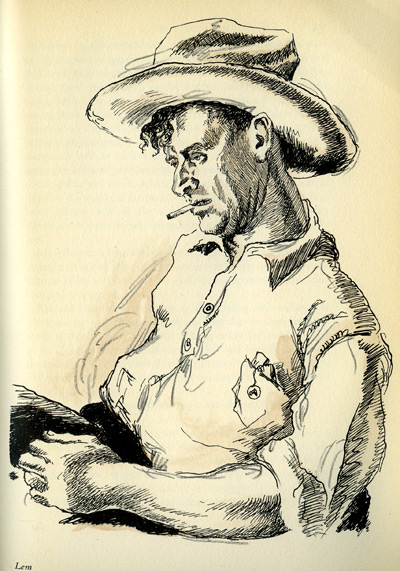

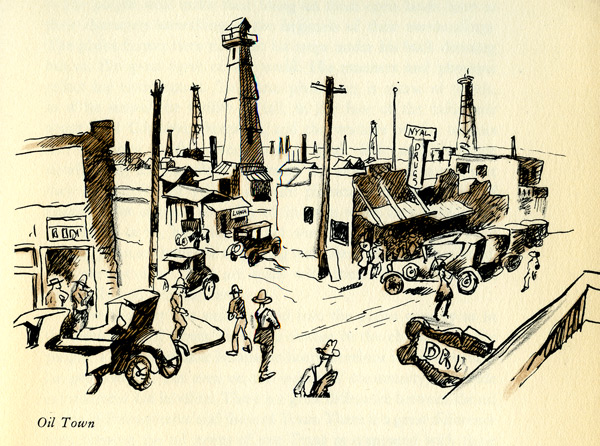

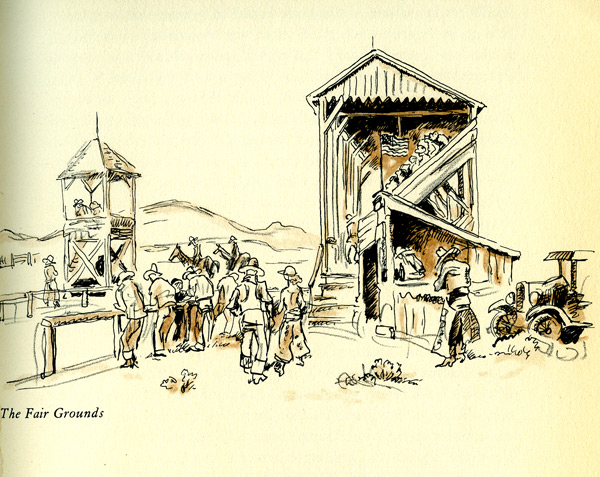

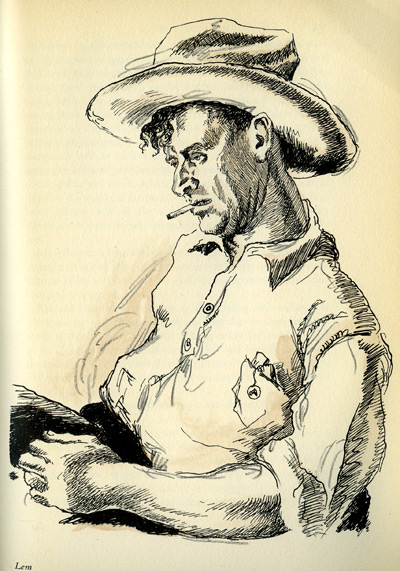

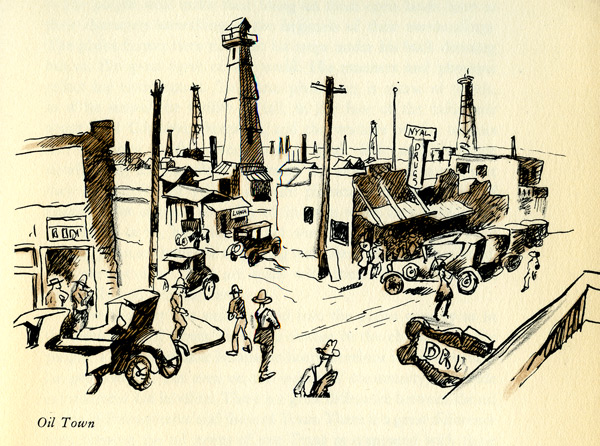

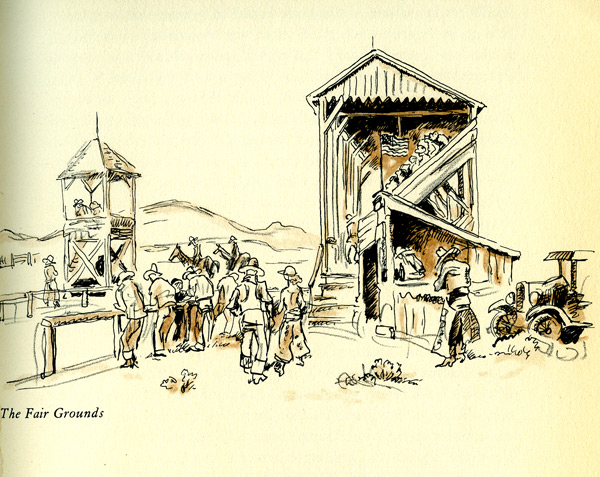

Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1937.

Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1937.

"Where does the West begin?

Strung in a zigzag pattern up and down the ninety-eight-degree line, there is a marked change of country which is observable wherever you journey westward, whether in the North, the middle country, or the South. About this line, though the exact distance from it is highly variable, the air becomes clearer, the sky bluer, and the world immensely bigger. There are great flat stretches of land in Louisiana, there are prairies in Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, but the experienced traveler in the United States does not confuse these with the West. Even though these more eastern prairies may present the same great vistas which are connected in our thoughts with the West, they lack the character of infinitude which one gets past the ninety-eight-degree line.

In the prairie lands, coming between the old forest country of the Middle West and the plains, one is able at times to see for great distances, but it is as if one were set down in the center of a big plate with elevated edges. There are definite ends to the horizon, which acts as an enclosure and sets a limit to things. In the West proper there are no limits. The world goes on indefinitely. The horizon is not seen as the end of a scene. It carries you on beyond itself into farther and farther spaces. Even the tremendous obstructions of the Rocky Mountains do not affect the sense of infinite extension which comes over the traveler as he crosses the plains. Unless you are actually in a pocket or a canyon, the Rocky Mountains rise in such a way, tier behind tier, that they carry your vision on and on, so that the forward strain of the eyes is communicated to all the muscles of the body and you feel actually within yourself the boundlessness of the world. You feel that you can keep moving forever without coming to any end. this is the physical effect of the West.

There are many people for whom this effect is unbearable, especially as it is manifested on the great plains. Cozy-minded people for whom life's values reside in little knicknacks which must be kept within easy reach, people for whom the sense of intimacy is necessary for emotional security, hate the brute magnitude of the plains country. All their familiar urges are inhibited by the great empty stretches of land and sky, by the immensity which reduces even a city to an anthill. Time and again on motorbusses and trains I've heard people complain of the monotony, the weariness, the oppressiveness of the plains. I've heard them groan over the misery of their journey.

For me the great plains have a releasing effect. They make me want to run and shout at the top of my voice. I like their endlessness. I like the way they make human beings appear as the little bugs they really are. I like the way they make thought seem futile and ideas but the silly vapors of the physically disordered. To think out on the great plains, under the immense rolling skies and before the equally immense roll of the earth, becomes a presumptuous absurdity. Human effort is seen there in all its pitiful futility. The universe is unveiled there, stripped to dirt and air, to wind, dust, cloud and the white sun. The indifference of the physical world to all human effort stands revealed as hard inescapable fact."

An Artist In America, by Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1937.

Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1937.

Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1937.

Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1937.

Monday, March 26, 2012 at 10:57PM Tweet

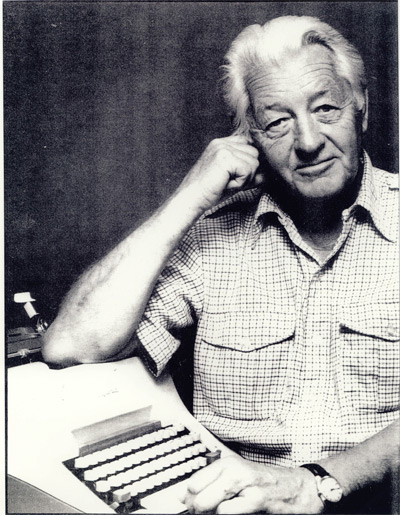

Monday, March 26, 2012 at 10:57PM Tweet  Photo courtesy of KUED.org

Photo courtesy of KUED.org