'The Proper Function of Man is to Live'

Tuesday, November 22, 2011 at 2:09PM Tweet

Tuesday, November 22, 2011 at 2:09PM Tweet By Jim Poulton

"I would rather be ashes than dust! I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze than it should be stifled by dry rot. I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet. The proper function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time." - Jack London, speaking to a reporter, shortly before his death in 1916

Jack London on his ranch in Sonoma County in 1914. Credit: Wikipedia

Jack London on his ranch in Sonoma County in 1914. Credit: Wikipedia

The chronicler of the Yukon, the defender of the cultures of the South Seas and the keen observor of the American West, Jack London died on this day in 1916 of renal failure. Born in 1876, he was a mere 40 years old when he died. But he packed into those 40 years a life many couldn’t live in 100. The son of an unmarried mother (it’s rumored his father was a pioneer in American astrology, William Chaney, and that his mother attempted suicide when Chaney refused to marry her), London took his name from a man she married in his early childhood, John London.

In his adolescence, London worked a variety of hard labor jobs, including going on patrol to capture poachers, working in a cannery, pirating oysters in San Francisco bay, and sailing the Pacific on a sealing ship. In 1894, he became a hobo, and was jailed for 30 days in New York for vagrancy.

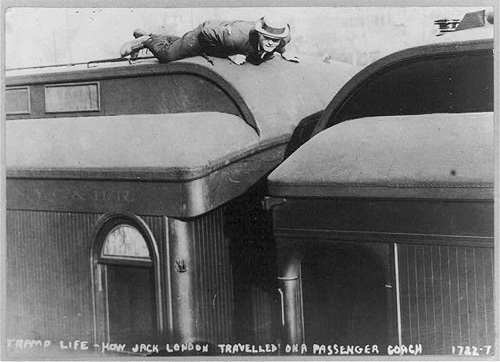

Jack London, showing how he traveled as a tramp. From his illustrated book, The Road. Credit: Library of Congress

Jack London, showing how he traveled as a tramp. From his illustrated book, The Road. Credit: Library of Congress

He spent the winter of 1897 in the Yukon, trying to find his fortune in the Klondike Gold Rush (where he developed scurvy) – all of which gave him no end of material for his later writing. He began publishing in 1899.

Sheep Camp in the Klondike. Jack London is believed to be the young man in the group on the right, second from left. Credit: Skagwaynews.com

Between 1899 and his death in 1916, he produced over fifty volumes of stories, novels and political essays, including Call of the Wild, White Fang, Sea Wolf and Klondike Gold Rush. His writings made him one of the most popular and well-known figures of his day. He was among the first writers to work with the movie industry, and a number of his stories were made into films.

Credit: Forum.Davidicke.com

Credit: Forum.Davidicke.com

During his thirties, London developed kidney disease, possibly related to late stage alcoholism. He died on November 22, 1916 in the place to which he had devoted the latter part of his life – Beauty Ranch in Glen Ellen, California, on the eastern slope of Sonoma Mountain: ‘Next to my wife,’ he said, ‘the ranch is the dearest thing in the world to me. … I write for no other purpose than to add to the beauty that now belongs to me. I write a book for no other reason than to add three or four hundred acres to my magnificent estate.’

Jack London working at his Beauty Ranch, 4 days before his death. Credit: London.sonoma.edu

Jack London working at his Beauty Ranch, 4 days before his death. Credit: London.sonoma.edu

London was well known for his prolific production, his eye for detail, and his observations of the richness of human experience. He seemed to absorb all of the little things that, when written, give you the feeling of actually being in the scene. In the excerpt below, from one of his later books, Valley of the Moon, the main character Saxon, who just moved into a Bay area cottage with her new husband Billy, talks about her family history with her friends Mary and Bert:

"Our cattle were all played out," Saxon was saying, "and winter was so near that we couldn't dare try to cross the Great American Desert, so our train stopped in Salt Lake City that winter. The Mormons hadn't got bad yet, and they were good to us."

"You talk as though you were there," Bert commented.

"My mother was," Saxon answered proudly. "She was nine years old that winter."

They were seated around the table in the kitchen of the little Pine Street cottage, making a cold lunch of sandwiches, tamales, and bottled beer. It being Sunday, the four were free from work, and they had come early, to work harder than on any week day, washing walls and windows, scrubbing floors, laying carpets and linoleum, hanging curtains, setting up the stove, putting the kitchen utensils and dishes away, and placing the furniture.

"Go on with the story, Saxon," Mary begged. "I'm just dyin' to hear. And Bert, you just shut up and listen."

"Well, that winter was when Del Hancock showed up. He was Kentucky born, but he'd been in the West for years. He was a scout, like Kit Carson, and he knew him well. Many's a time Kit Carson and he slept under the same blankets. They were together to California and Oregon with General Fremont. Well, Del Hancock was passing on his way through Salt Lake, going I don't know where to raise a company of Rocky Mountain trappers to go after beaver some new place he knew about. Ha was a handsome man. He wore his hair long like in pictures, and had a silk sash around his waist he'd learned to wear in California from the Spanish, and two revolvers in his belt. Any woman 'd fall in love with him first sight. Well, he saw Sadie, who was my mother's oldest sister, and I guess she looked good to him, for he stopped right there in Salt Lake and didn't go a step. He was a great Indian fighter, too, and I heard my Aunt Villa say, when I was a little girl, that he had the blackest, brightest eyes, and that the way he looked was like an eagle. He'd fought duels, too, the way they did in those days, and he wasn't afraid of anything.

"Sadie was a beauty, and she flirted with him and drove him crazy. Maybe she wasn't sure of her own mind, I don't know. But I do know that she didn't give in as easy as I did to Billy. Finally, he couldn't stand it any more. Ha rode up that night on horseback, wild as could be. 'Sadie,' he said, 'if you don't promise to marry me to-morrow, I'll shoot myself to-night right back of the corral.' And he'd have done it, too, and Sadie knew it, and said she would. Didn't they make love fast in those days?" – Valley of the Moon, Book I, Chapter XIII

Jack London’s gravesite. Credit: London.sonoma.edu

Jack London’s gravesite. Credit: London.sonoma.edu

Reader Comments